Habitat Loss

go.ncsu.edu/readext?830121

en Español / em Português

El inglés es el idioma de control de esta página. En la medida en que haya algún conflicto entre la traducción al inglés y la traducción, el inglés prevalece.

Al hacer clic en el enlace de traducción se activa un servicio de traducción gratuito para convertir la página al español. Al igual que con cualquier traducción por Internet, la conversión no es sensible al contexto y puede que no traduzca el texto en su significado original. NC State Extension no garantiza la exactitud del texto traducido. Por favor, tenga en cuenta que algunas aplicaciones y/o servicios pueden no funcionar como se espera cuando se traducen.

Português

Inglês é o idioma de controle desta página. Na medida que haja algum conflito entre o texto original em Inglês e a tradução, o Inglês prevalece.

Ao clicar no link de tradução, um serviço gratuito de tradução será ativado para converter a página para o Português. Como em qualquer tradução pela internet, a conversão não é sensivel ao contexto e pode não ocorrer a tradução para o significado orginal. O serviço de Extensão da Carolina do Norte (NC State Extension) não garante a exatidão do texto traduzido. Por favor, observe que algumas funções ou serviços podem não funcionar como esperado após a tradução.

English

English is the controlling language of this page. To the extent there is any conflict between the English text and the translation, English controls.

Clicking on the translation link activates a free translation service to convert the page to Spanish. As with any Internet translation, the conversion is not context-sensitive and may not translate the text to its original meaning. NC State Extension does not guarantee the accuracy of the translated text. Please note that some applications and/or services may not function as expected when translated.

Collapse ▲Forest Lost to Urban Development

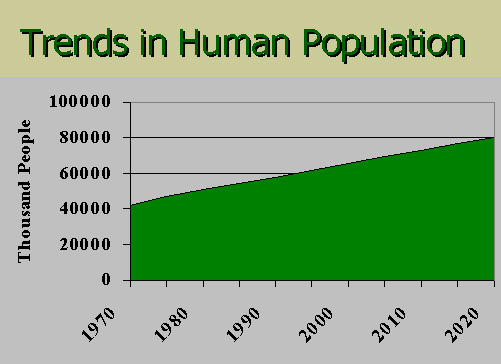

The human population in the southeastern United States is expected to double between the years 1970 and 2020, from about 40 million to 80 million people.

The human population of the Southeast will reach 80 million by 2020.

Running parallel to this increase in population is drastic wildlife habitat loss across the region. From 1982 to 1997, North Carolina lost 1,001,000 acres or 5.9 percent of its total forest area to land conversion related to population growth and urbanization. Researchers predict an additional loss of 5.5 million forested acres in North Carolina by 2040.

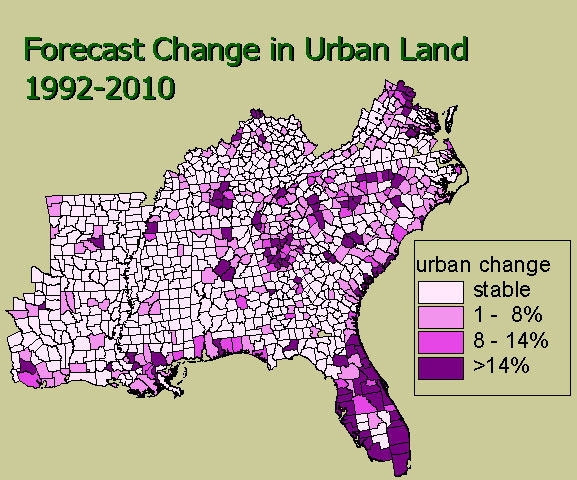

The South will experience rapid urbanization in the coming decades.

Extensive forest will be cleared during urbanization.

Many animals disappear following land clearing and construction.

As land is converted from forest to urban use, it becomes unsuitable for many specialized wildlife species, especially animals that require large tracts of unbroken forest. Pileated woodpecker, black-and-white warbler, scarlet tanager, and wood thrush are examples of species that will disappear as areas are built up. Other species, including white-tailed deer, raccoon, and gray squirrel, adapt well to the land changes. Even some birds like house finches, American robins, and northern cardinals are common in developed habitats. These adaptable species are able to make use of various food and cover sources available in cities.

Cleared Forest Replaced with Non-Native Plants

Areas cleared of forest to make room for buildings and neighborhoods are replanted with a very limited variety of non-native plants. These landscaped areas are poor quality habitat because they contain low plant diversity, few native plants, and poor plant structure. Bird and butterfly species that require habitats containing a diversity of native plants cannot sustain their populations in these typical landscapes.

Remaining Forest is Degraded and Fragmented

Snakes, turtles, and other wildlife are killed by passing cars.

Small patches of forest or native plant habitats are usually left after an area is urbanized; these habitats commonly occur in parks or other natural areas, along streams, or on steep slopes that couldn’t be developed. These isolated patches of forest, however, will not sustain populations of many wildlife species. Over time, many factors contribute to degradation of the remnant habitats. Invasive plants creep into the forest from all sides, human users and their pets compact soil and disturb wildlife, and natural forces such as wildfire are not allowed to run their course. Additionally, the populations of animals present in the patches are at risk of local extinction because they are isolated from other populations. Individual animals that attempt to move from one patch to another are often run over by cars or eaten by cats or other predators.

Every Little Bit Helps

Each individual home or property owner can help conserve wildlife habitat in urban areas by landscaping with native plants following proper design principles. When a number of people take action over a large area, across a neighborhood, for example, they can help connect small blocks of habitat and allow animals to more easily move across an urbanized region.

**Forecast changes in population and forest and urban land cover are from the Southern Forest Resource Assessment.